Exhibition place:First Floor, Fashion Gallery, China Silk Museum

Exhibition time:2020.9 - 2020.11

Cristóbal Balenciaga (1895–1972) was one of the most revered fashion designers of the 20th century. His clothes were characterised by their sculptural quality, deft manipulation of textiles and dramatic use of colour and texture. His contemporaries called him The Master.

One hundred years after Balenciaga established his first dressmaking business in northern Spain, this exhibition reveals what made Balenciaga's work so exceptional and how it continues to shape fashion – in couture and on the high street – today.

Drawing on the V&A's extensive collection of Balenciaga from the 1950s and 60s, the displays on the temporary exhibition hall explore his craftsmanship, his workrooms and the experience of being a client. The Galaxy Hall looks at Balenciaga's impact on later generations of fashion designers, those with whom he worked closely and those working within the same tradition today.

Cristóbal Balenciaga was born in 1895 in Getaria, a fishing village in the Basque region of northern Spain. He was introduced to fashion by his mother who was a seamstress. Aged twelve, he began an apprenticeship at a tailor's in the neighbouring fashionable resort of San Sebastian. There, ten years later, he opened his first fashion house in 1917.

Balenciaga's training set him apart. Unlike most couturiers he was skilled in every stage of the making process: designing, cutting, tailoring and dressmaking. His early work drew on French designers such as Madeleine Vionnet and Coco Chanel, who became close friends. His Spanish heritage informed his designs throughout his career.

In 1937, during the Spanish Civil War, Balenciaga established a couture house on the Avenue George V in Paris. He would remain there for the rest of his fifty-year career while maintaining strong ties to Spain, where he ran a sister label under the name Eisa.

Regional dress

Spanish costume was a recurring influence on Balenciaga. As early 20th-century Spain became urbanised, anthropologists and artists strove to record traditional customs before they died out. Balenciaga owned Isabel de Palencia's anthology of regional costumes and would have seen the photographs of his Basque contemporary José Ortiz-Echagüe. This evening gown made for his good friend Francine Weisweiller shows a debt to Valencian dress.

BVA.248

Evening dress

Silk organza, with embroidery by Lesage

Cristóbal Balenciaga, Paris, 1960

V&A: T.17-2006

China Through Flamenco

The brightly-coloured, floral embroidery on this figure-hugging, silk dress is reminiscent of the style found on Manila shawls. These fringed shawls were often embroidered in Canton/Guangzhou, China. They were prized possessions commonly worn by flamenco dancers and women throughout Spain for festivals and special occasions from the 19th century.

Balenciaga designed the dress to be full-length, making the most of the unusual pattern. This shorter version was probably made at the client's request.

BVA. 030

Cocktail dress

Wild silk, with embroidery by Lesage

Cristóbal Balenciaga, Paris, 1960–2

Given by Viscountess Lambton

V&A: T.27-1974

The Ateliers

Behind the scenes at his famous fashion house in Paris, The Master created his collections. Over two floors at the back of the building were the ateliers or workrooms. At the height of Balenciaga's success, he had four tailoring workshops, four for dressmaking and two dedicated to millinery. The head of each supervised a team of 30 to 40 highly skilled cutters, seamstresses and fitters. Overall Balenciaga employed nearly 500 staff in Paris.

He assigned each design to a particular atelier. Staff prepared a prototype garment or toile in cheap calico fabric to fit a particular house model. Balenciaga was unusually attentive for a couturier. Dressed in a white coat, he studied each piece and made alterations to meet his exacting standards. The garment was then made up in the chosen fabric and allocated a number by which it could be identified.

Working with fabric

Most designers start with a sketch and then seek out a material. Balenciaga began with the fabrics and designed around them. 'It is the fabric that decides,' he said. He revelled in the variety and quality of fabrics available in Paris and forged close working relationships with the many suppliers of luxury textiles, embellishments and accessories.

Despite government subsidies offered to those who purchased French textiles, Balenciaga also chose to buy from manufacturers in Italy, Switzerland and the UK. He was known as a discerning and knowledgeable client, open to experimentation and new developments.

Fantastical fabrics

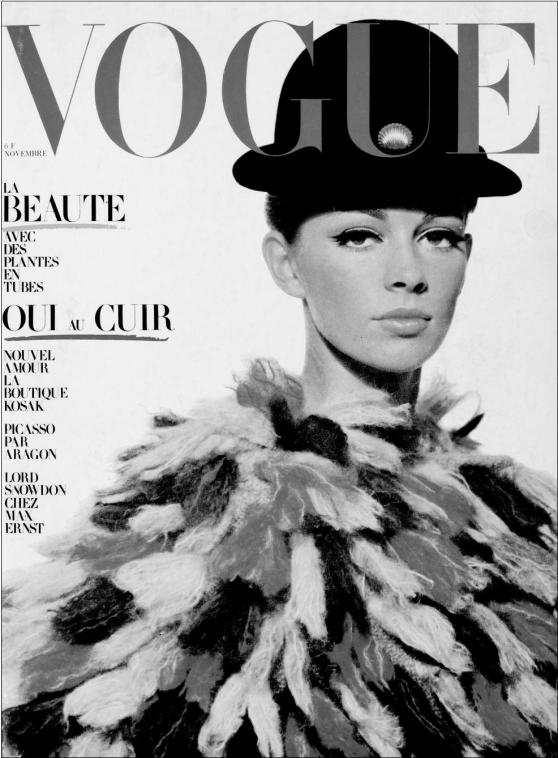

Ascher textiles devised this hand-tufted mohair known as Papacha in conjunction with Balenciaga. Featured on the front cover of French Vogue, Balenciaga's three-quarter length coat is a simple T-shape with no collar or cuffs. It completely hides the wearer's figure and foregrounds the fabric itself. The multicoloured tufts, knotted by hand into the mohair ground fabric, are made up of two or three different colours of mohair yarns.

B86

Vogue Paris, November 1964

Photograph by Helmut Newton

© Vogue Paris. The Helmut Newton Estate / Maconochie

Photography

Cut and construction

Balenciaga's training in tailoring set a high standard for his workrooms. He insisted on perfection. Sleeves were an obsession. Balenciaga believed they were fundamental to the perfect fit. When the sleeves were not right, he could be heard shouting in Spanish la manga! ('the sleeve'), before picking the garment apart and starting again.

The well cut Balenciaga suit became a staple of many a fashionable woman's wardrobe. He introduced a looser-fitting 'easy line', three-quarter length sleeves and the stand-away collar, ideal for displaying a string of pearls. His pared back designs of the 1960s used innovative pattern cutting to create garments with few seams.

Fabric

The strong architectural shape of the dress photographed here relies on its fabric: a stiff silk gazar which stands away from the body and holds its form.

The main dress is made of a single piece joined at the back with no side seams – a characteristic of Balenciaga's designs. A second panel of fabric hangs from the shoulders and is secured with bar tacks under the arms, creating the illusion of a loose, unstructured garment. Underneath, however, a stiff corset (visible in the X-ray) ensures a secure fit.

As in many Balenciaga designs, the plain front of this 'Tulip' dress (as critics soon dubbed it) reserves interest for the back, with its large bow reminiscent of Japanese kimono.

BVA.024.01

Replica toile (prototype garment)

Calico

Made by Elizabeth Nsubuga, London College of Fashion, 2016

V&A: NCOL.693-2016

Cut

A virtuoso example of pattern-cutting, the main body of this woman's evening dress is cut from a single piece of fabric joined at the centre back. There are no side seams. Two dress weights at the front, visible in the x-ray, ensure it falls correctly. The neck of the cape is painstakingly pieced to ensure a soft line which stands away from the body.

This ensemble typifies the increasing simplicity and abstraction of Balenciaga's later work. It relies on a deep knowledge of the fabric which determines the sculptural shape. Although strikingly modern, the design echoes mantles and soutanes worn by Catholic clergy in Spain and elsewhere.

BVA.036

Evening dress and cape

Silk

Cristóbal Balenciaga, Paris, 1967

Given by Mrs Loel Guinness

V&A: T.39&A-1974

Dressmaking

Dressmaking took place in the workshops dedicated to flou or soft fabrics, which require mastery of different skills from tailoring. Balenciaga trained as both dressmaker and tailor, and was influenced in his early career by French designers such as Madeleine Vionnet and Madame Grès. They created dresses not by flat pattern-cutting, but by draping fabric on a mannequin or a body in 360 degrees. Balenciaga was known for this skill, too.

Balenciaga's evening dresses are more traditional and romantic than his daywear. He drew on a wide range of sources, including non-Western clothing, and historical and ecclesiastical dress.

Historically inspired

Balenciaga encountered luxury fashion from an early age. His mother was a seamstress who altered the Paris gowns of wealthy clients such as the Marquesa de Casa Torres. He later collected garments and magazines from the 19th century for inspiration. The bustle-like back, heavy silk satin and sumptuous embroidery in this evening dress reflect this deep-rooted interest.

BVA.010

Evening dress

Satin, with embroidery of silk and gold paillettes by Rébé

Cristóbal Balenciaga, Paris, 1955

Bequeathed by Mrs Fern Bedaux

V&A: T.758-1972

Hats

Many couturiers outsourced their hat-making, but at Balenciaga's premises in Paris there were two ateliers made for millinery. Balenciaga did not design the hats himself but worked closely with his hat designers: the Franco-Russian milliner Wladzio d'Attainville and later the Spaniard Ramón Esparza.

Balenciaga's hats were some of the most elaborate in Paris. So much so that during the Second World War the authorities shut down his millinery workshops, accusing him of exceeding the fabric allowance under austerity measures and encouraging the fashion for extravagant millinery. His hats of the 1950s and 60s grew increasingly surreal, as they played with scale, shape and unusual materials.

BVA.042

Cream spiral hat

Silk

Cristóbal Balenciaga (Eisa label), Spain,1962

V&A: T.146-1998

Modernity with tradition

Founded in the 1920s, the French firm Lesage was known for its virtuoso embroidery. Like Balenciaga, François Lesage, who ran the house in the 1950s and 60s, wanted to introduce unusual materials into couture. These samples include designs made in plastic by Paco Rabanne. They are marked with Balenciaga's name to ensure they were kept exclusively for his use on garments such as this coat.

BVA.060

Coat

Silk, with decorations by Paco Rabanne and embroidery by

Lesage

Cristóbal Balenciaga, Paris, 1961

Given by Mrs Loel Guinness

V&A: T.24-1974

Layers of craftsmanship

To create this precisely gradated design, the embroiderer has built up layers of beading on a piece of silk organza dip-dyed pink. The coat was constructed first. Then the coloured stitching was added (visible on the back), then white pearls (in a seemingly haphazard 'vermicelli' design), and then teardrop and pink feather-shaped sequins. Finally large pearls were added and Swarovski crystals. The nearby video shows embroiderers recreating the beading at Lesage today.

BVA.070

Evening coat

Silk organza, with embroidery and beading by Lesage

Cristóbal Balenciaga, Paris, 1967

V&A: T.38-1974

From the late 1930s, Balenciaga was a huge international success. The House of Balenciaga at 10 Avenue George V was the most exclusive and expensive couture establishment in Paris. The façade, displaying abstract sculptures, revealed nothing of the visionary fashion being created inside. Clients entered through a large wooden door, then took a red leather-padded lift up to the third floor. There they saw models parade the designs or had garments fitted.

Twice a year the new collections were shown in the Grand Salon. Balenciaga courted controversy in 1956, when he barred the press from his initial showings. Concerned with protecting his designs from illegal copies, he made journalists wait a month before they could view and publish them. His disciple Hubert de Givenchy joined him, and for ten years, the two were such beacons of the fashion world that foreign journalists made additional trips to Paris just to cover the Balenciaga and Givenchy shows.

Salon shows

Balenciaga's seasonal collections contained between 150 and 200 looks – from evening wear to sportswear. His designs, which evolved gradually each season, revolutionised the female silhouette. Volume ballooned at the hem, then moved towards the back, the waist was eliminated and his shapes became increasingly abstract.

The parade of new designs was a serious affair with no music, and lasted up to an hour and a half. Balenciaga chose unconventional models whom he trained himself. They walked in a 'haughty trance', according to one fashion editor, avoiding eye contact with their audience. Balenciaga remained behind a curtain. He refused to give his designs names, unlike other designers, and would not bow at the end of the show, preferring the clothes to speak for themselves.

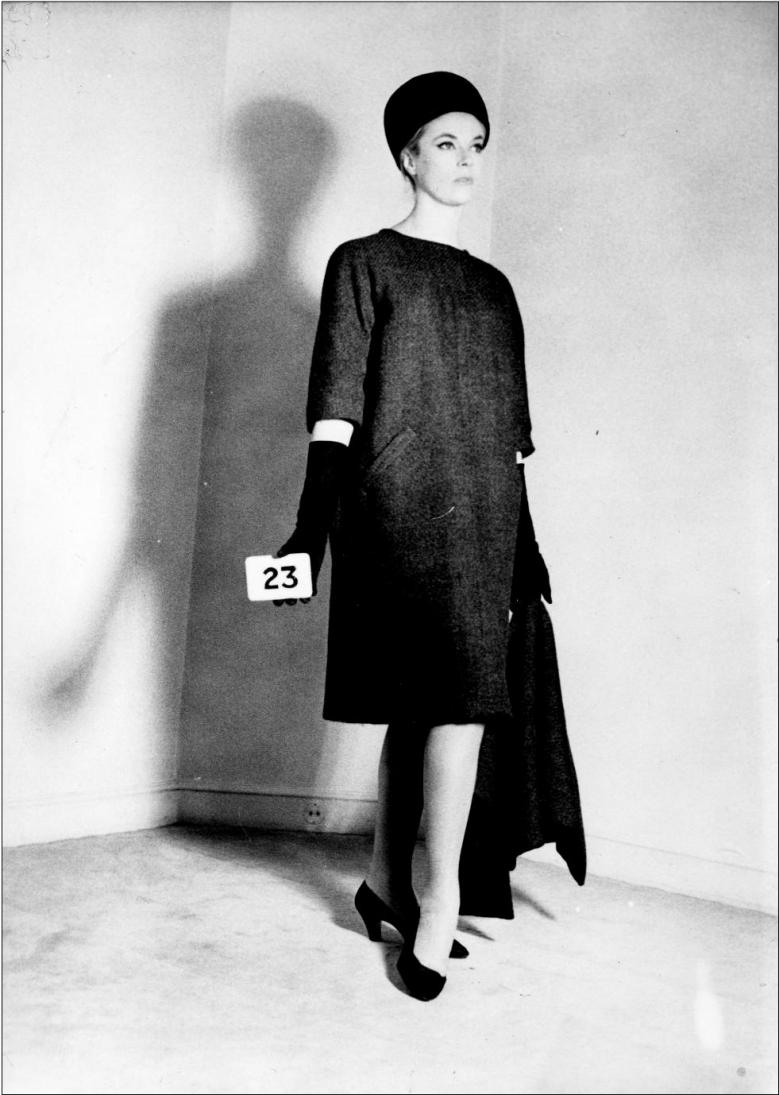

The unsexy sack

'It's Hard to be Sexy in a Sack!' cried the Daily Mirror in 1957. Balenciaga's 'sack' dress shocked when he first presented it in the late 1950s. Its straight line contrasted sharply with the still dominant hourglass shape favoured by his main competitor, Christian Dior. In eradicating the waist altogether, Balenciaga anticipated the popular shift dresses of the 1960s.

B19

Model wearing 'sack' dress, 1958

Photograph by Tom Kublin for Balenciaga

Courtesy of the Balenciaga Archives, Paris

Baby doll dress

Introduced in 1958, the 'baby doll' dress controversially hid the shape of the woman's figure when made in opaque fabric. In this example Balenciaga both reveals and conceals the body. The sheer, Chantilly lace hangs loosely over a fitted inner sheath.

Balenciaga's use of black lace is indebted to the mantilla, a shawl which Spanish women use to cover their heads and shoulders during religious ceremonies. By the mid-19th century, mantillas had become symbolic of Spain.

BVA.020

Cocktail dress

Crêpe de chine, satin and lace by Marescot

Cristóbal Balenciaga, Paris, 1958

V&A: T.334-1997

The Amphora line

A further development of the semi-fitted silhouette, this evening dress is sometimes called 'The Amphora Line', referring to the curved shape of Greek vases. The complex shape is formed by two pieces of fabric which join at the centre front and continue around the back to fall in long gathered strips forming a decorative bow.

B21

Model wearing Amphora Line evening dress, 1960

Photograph by Tom Kublin for Balenciaga

Courtesy of the Balenciaga Archives, Paris

The clients

Balenciaga's couture clients were among the best-dressed and wealthiest women in the world. They chose their new clothes in Paris seasonally and had them made to measure.

If the cost of his Paris salon was out of reach, there were other ways to buy a Balenciaga design. Some were sold less expensively under Balenciaga's label Eisa in Spain, where labour costs were lower and cheaper fabrics might be used. Others were licensed for high-end department stores such as Harrods to copy. Another practice was to have copies made by a local dressmaker. Some Balenciaga clients duplicated their couture wardrobes this way so they never had to pack when travelling.

As fashion moved away from an emphasis on couture, critics began to question Balenciaga's relevance at the end of his long career. Yet throughout the 1950s and 1960s, his business continued to flourish and he retained the loyalty of his international clientele.

The Hollywood actress

Ava Gardner moved to Madrid in the 1950s. She found Spain 'unspoiled . . . dramatic . . . and so god-damn cheap to live in, that it was almost unbelievable'. She bought Balenciaga designs both in Paris and at Eisa, which may have appealed to what she called her 'frugal side'. Gardner spent her final years living around the corner from the V&A and donated several of her clothes to the museum.

B48

Hollywood star Ava Gardner in Balenciaga dress, 1960

From the film The Angel wore Red

Photo by Silver Screen Collection/Getty Images

Added glamour

The photograph shows an earlier version of this coat, before actress Ava Gardner adapted it by adding ostrich feathers. The embroidered fabric and scalloped edge are similar to – but not the same as – a design in the Paris collections, so the fabric may be Spanish. Gardner referred to her couture garments as her 'babies' and insisted on opening her wardrobes daily to let them 'breathe'.

B49

Hollywood star Ava Gardner wearing the evening coat,

mid-1960s

Photograph by Oldrich Karasek, Camera Press, London

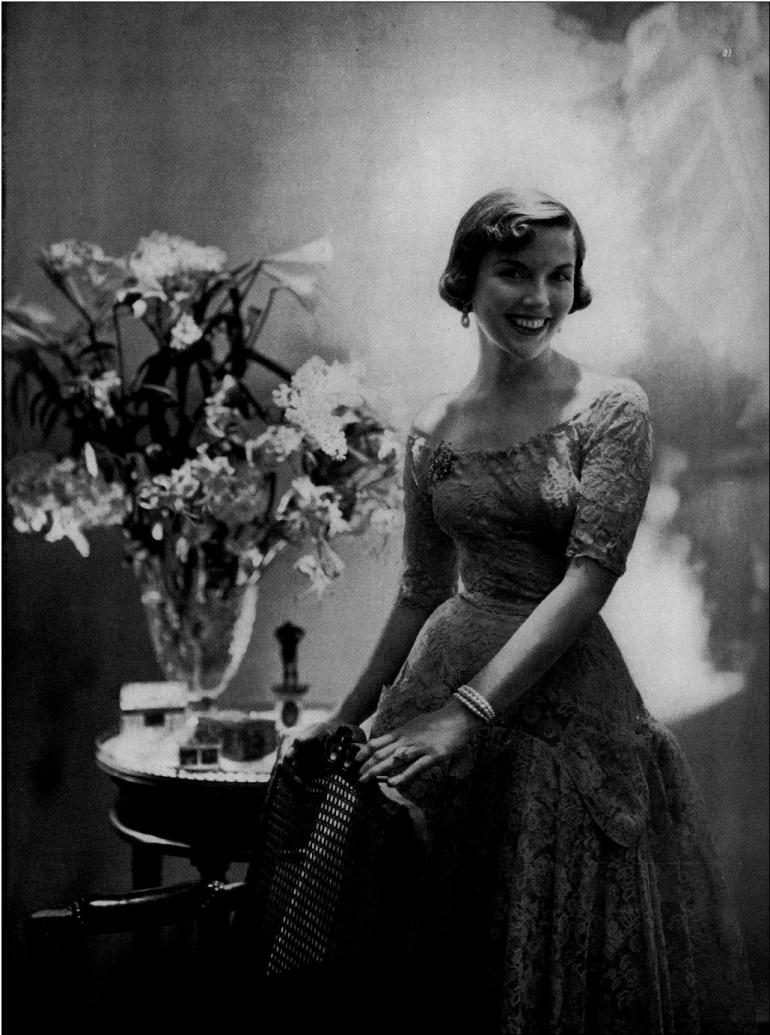

Everyday couture

American client Anne Bullitt lived in Madrid with the second of her four husbands. These simple dresses are examples of the more everyday production of the Eisa house, not all of whose clients were confident trendsetters. The quality of dressmaking is good, with hand-finished hems and seams, but it is not to the extremely high standard of the Parisian house.

B47

Mrs Anne Bullitt Biddle, 1950

Photograph by Cecil Beaton for American Vogue

Haute couture clients

Maintaining a couture wardrobe required time as well as money. Each garment needed up to three fittings: the first to take measurements, the second to fit the toile, and the third for adjustments in the final fabric. For regular clients, a dressmaker's stand was padded to their exact dimensions, so that first fittings were not essential.

The close relationship between couturier and client often lasted years. For Balenciaga's loyal clientele, the closure of the fashion house in 1968 marked the end of an important part of their lives, and his death just four years later, the end of an era.

An American client

Parisian couture after the Second World War owed much of its success to wealthy Americans such as Elizabeth Parke Firestone. Her husband was heir to the profitable Firestone Tire Company. A faithful client of both Balenciaga and Christian Dior, she favoured the colour blue and had very particular demands about her garments' fit, suggesting to her personal saleswoman the addition of a belt or change to the shoulders.

B53

Elizabeth Parke Firestone, 1929

Lithograph of portrait by Philip de Laszlo

From the Collections of Henry Ford, Dearborn, Michigan

A flock of coats

Balenciaga presented this dramatic evening coat with a skirt, but Pauline de Rothschild, who had long, slender legs, wore hers with silk trousers. The designer made several similar creations for her to wear at Château Mouton Rothschild, the country house where she and her husband entertained. She referred to the coats as mes moutons or 'my sheep'.

B54

Pauline de Rothschild wearing her 'mouton noir' coat, 1963

Photograph by Horst P. Horst for American Vogue

© Condé Nast

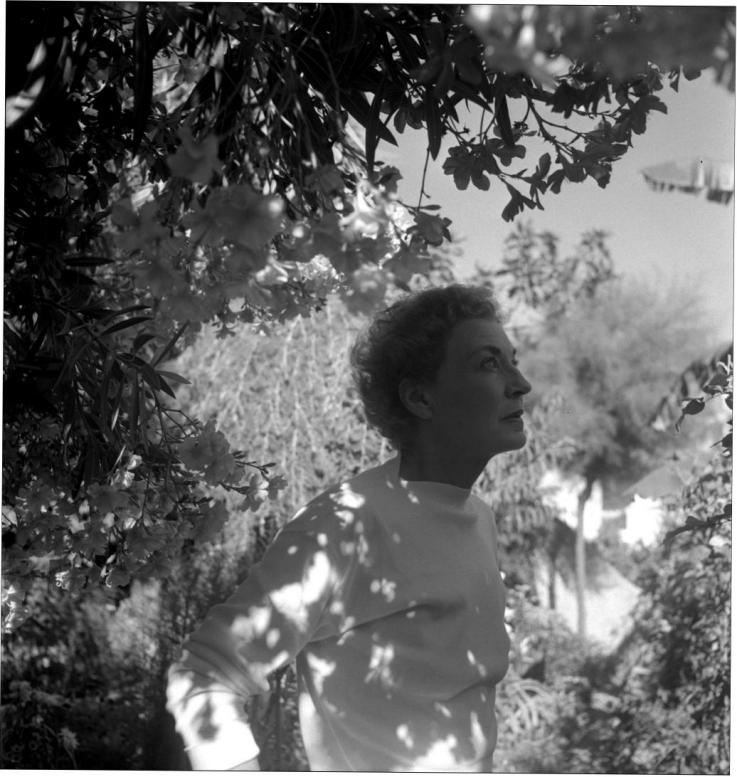

The end of an era

Countess Mona Bismarck was a loyal client of Balenciaga for 30 years. One season she bought 80 garments. Even her gardening shorts came from the house. Fashion editor Diana Vreeland was staying with Bismarck when Balenciaga closed his fashion house. She recalled: 'Mona didn't come out of her room for three days . . . It was the end of a certain part of her life!'

B52

Client Mona Bismarck wearing a Balenciaga gardening outfit, Capri, 1967–8

Photograph by Cecil Beaton

© The Cecil Beaton Studio Archive at Sotheby's

Cristóbal Balenciaga's innovative pattern-cutting, use of new materials and bold architectural shapes have been greatly influential. French designer Emanuel Ungaro, who trained with Balenciaga, said it was he who 'laid the foundations of modernity' in fashion. His high standards and impeccable craftsmanship remain an aspiration for many designers.

The closure of Balenciaga's fashion house in 1968, and his death four years later, marked the end of an era. It coincided with the rise of designer ready-to-wear clothing which came to dominate fashion.

Many of the garments on this floor are high-end ready-to-wear rather than haute couture: they are created by a named designer but are machine-made in multiples, rather than made by hand for a specific client. Towards the centre of the room are designers who worked with Balenciaga or followed him closely. Many designed for his former clients. Towards the outer edge are contemporary designers who work in the same tradition or cite him as an influence on their work today.

Pay attention to us

×

Pay attention to us

×