Exhibition place:Temporary Gallery, China National Silk Museum

Exhibition time:2019.9 - 2020.1

About Dior

1. About Dior

1.1 Childhood and the garden

Christian Dior was born in Granville, a seaside town on the coast of Normandy, France. He was the second of five children born to Maurice Dior, a wealthy fertilizer manufacturer (the family firm was Dior Frères), and his wife, formerly Madeleine Martin. He had four siblings: Raymond (father of Françoise Dior), Jacqueline, Bernard, and Catherine Dior. When Christian was about five years old, the family moved to Paris, but still returned to the Normandy coast for summer holidays.

Christian Dior spent most of his childhood in Villa Les Rhumbs, whose gardens were transformed in to the lushest of Edens by Christian’s mother, Madeleine.

“I drew women-flowers, soft shoulders, fine waists like liana and wide skirts like corolla,” said Christian Dior, of the designs that were to become his ‘New Look’. These shapes were influenced not just by an accentuated female form, but by botanical anatomy – the corolla is the tube formed by the petals at the base of a flower – and whole flowers, such as the tulip. For one of the most famous moments of fashion history to hinge on a petal is no small thing, but for Dior it was a natural progression from his other great passion: gardens.

Madeleine’s rose garden – planted with more than 20 different species – became a source of great inspiration for the scents that Dior would go on to create, as did the scrambling jasmine, honeysuckle and passionflower which adorned the garden walls. “My life and style owed almost everything to Les Rhumbs,” the designer said.

1.2 From Political Science to Art

Although Dior was passionate about art and expressed an interest in becoming an architect, he submitted to pressure from his father and, in 1925, enrolled at the École des Sciences Politiques to begin his studies in political science, with the understanding that he would eventually find work as a diplomat.

In 1928 after graduation, Dior left school and receivedfinancial support from his father to open a small art galleryon the condition that the family name would not appear above the gallery door.

In the few years it was open, Dior's gallery handled the works of such notable artists as Georges Braque, Pablo Picasso, Jean Cocteau and Max Jacob. He was forced to close the gallery in 1931.

Although the gallery was closed three years later, those were the time Dior received precious friendship of his close friends, who supported him from darkest time of this life, the same year that included the deaths of both his older brother and mother and the financial collapse of his father's business.

1.3 The Path to Fashion

Following the closing of his gallery, Dior began to make ends meet by selling his fashion sketches, and in 1935, landed a job illustrating the magazine Figaro Illustré.

From 1937, Dior was employed by the fashion designer Robert Piguet, who gave him the opportunity to design for three Piguet collections. Dior would later say that 'Robert Piguet taught me the virtues of simplicity through which true elegance must come.' One of his original designs for Piguet, a day dress with a short, full skirt called "Cafe Anglais", was particularly well received.Whilst at Piguet, Dior worked alongside Pierre Balmain, and was succeeded as house designer by Marc Bohan – who would, in 1960, become head of design for Christian Dior Paris.Dior left Piguet when he was called up for military service.

1.4 The Fashion House

In 1946 Marcel Boussac, a successful entrepreneur known as the richest man in France, invited Dior to design for Philippe et Gaston, a Paris fashion house launched in 1925. Dior refused, wishing to make a fresh start under his own name rather than reviving an old brand.December 1946, with Boussac's backing, Dior founded his fashion house.

The New Look: February 12, 1947

Seventeen months after the end of the Second World War, Christian Dior presented his first collection. It swept away the wartime, masculine style with padded shoulders and knee-length skirts, replacing it with an ultra-feminine silhouette that accentuated the bosom and waist, and featured soft shoulders and long, full skirts. Carmel Snow, editor of Harper’s Bazaar, dubbed it the “New Look.” Christian Dior said it was the “look of peace… it reflects the times.”

The New Look was also a new feel, quite unlike wearing wartime fashions. Fitted cloth hugged and securely wrapped the torso and arms. Excessive yardage had a sensuous weight as long skirts moved fluidly when walking and pooled luxuriously when sitting. Vogue announced that, “Dior spread the thought that every woman in a Dior dress, or even a copy of a Dior dress, was a figure of fashion.”

The Ateliers

Haute couture ateliers, or workrooms, are organized around the methods and skills needed to transform fashion sketches into three-dimensional garments. The flou (dressmaking) relies on techniques of draping and the manipulation of delicate silks and lightweight chiffons and lace. The tailleur (tailoring) requires different techniques to mould and shape heavier textiles such as wool.

Marguerite Carré, Christian Dior’s technical director, distributed the designs to the première/premier (lead hand), whose taste and specialty she felt would best interpret the “poetic mood” of the sketch. Together with their assistants (demi and petites mains), the atelier brought the garments to life.

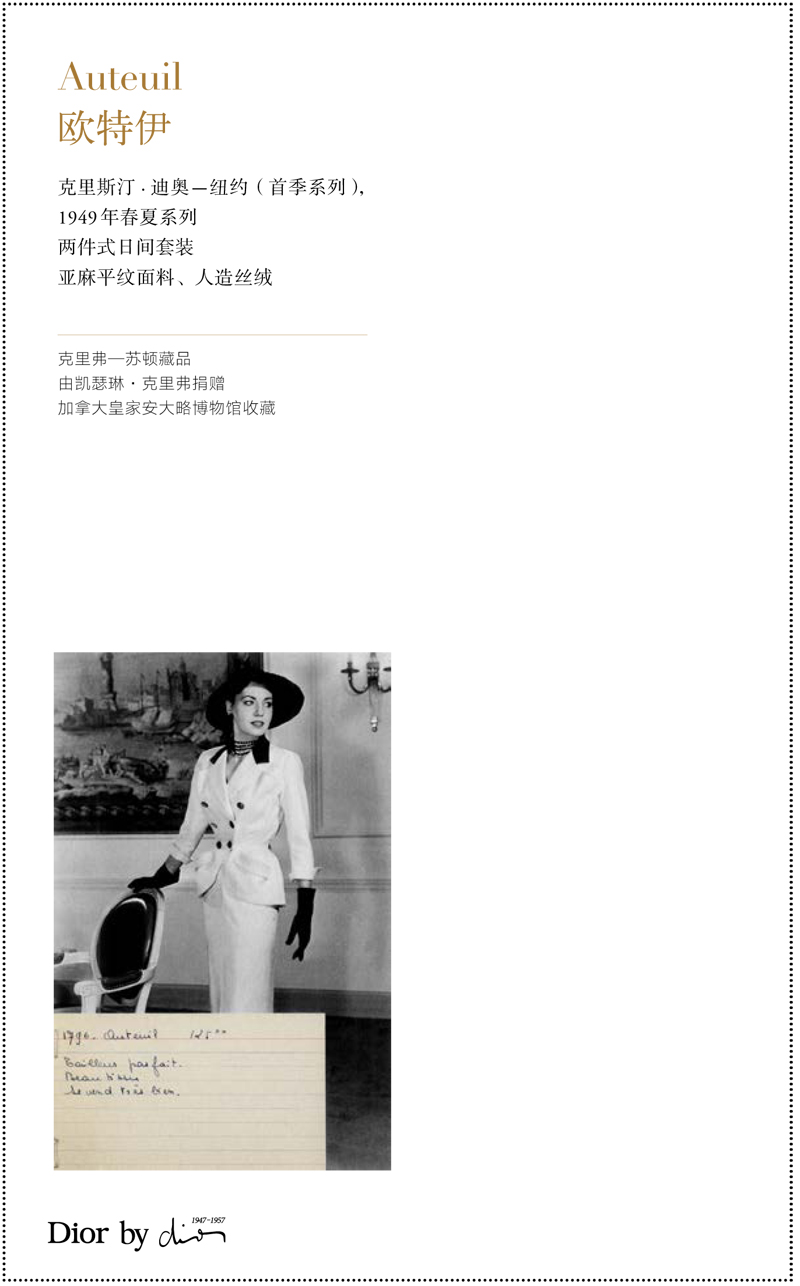

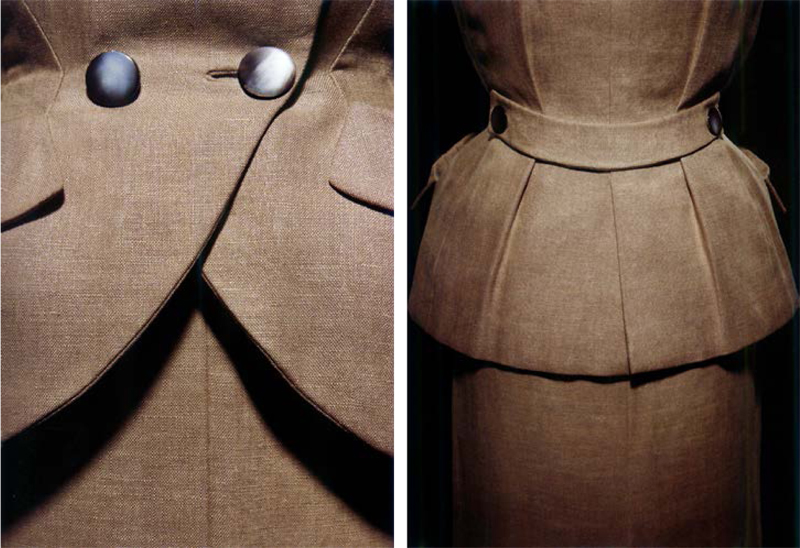

Christian Dior’s daytime suits and dresses were designed for women on the move. Prioritizing precision tailoring over draping, he made sure the Dior woman looked sleek and feminine and was not hindered by her clothing.

Sleeves

Fitted sleeves with soft, rounded shoulders were achieved by cutting the sleeve and body in one piece. Triangular bias gussets, inserted in the armpit, allowed for close fit and movement.

Pleats

Pleats in skirts offered practical and casual elegance. The ateliers developed new methods of making pleats that required more textile yardage, and more time sewing than a traditional folded pleat.

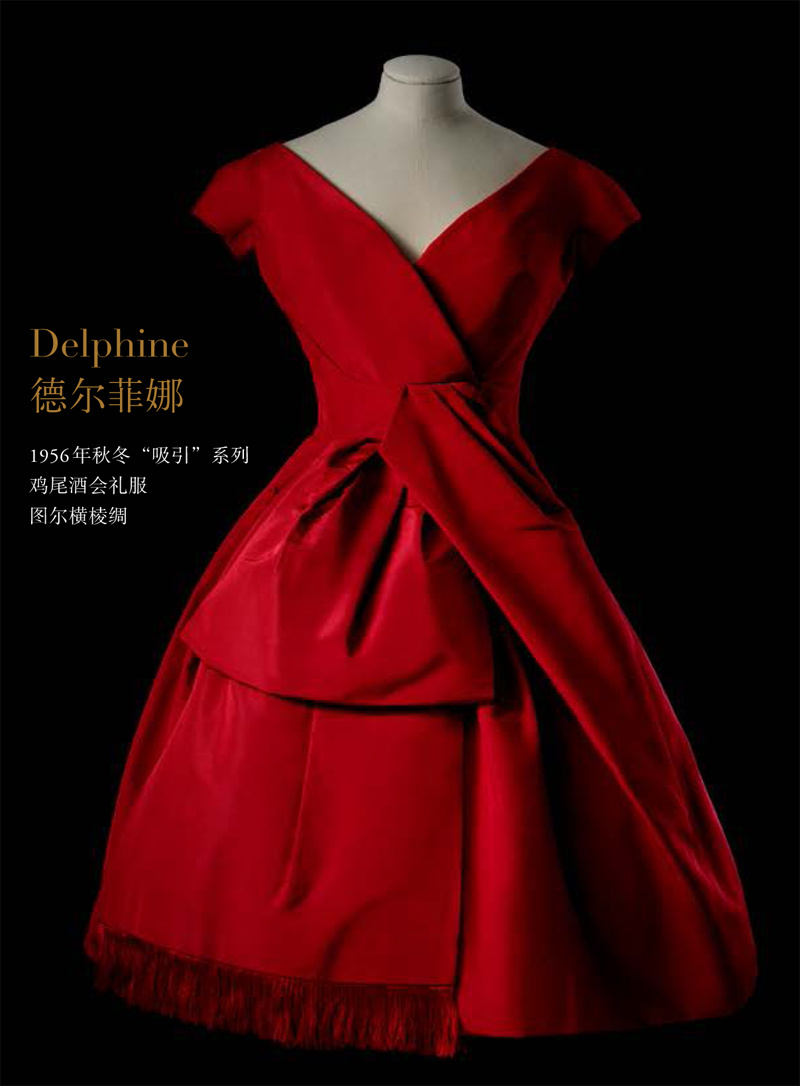

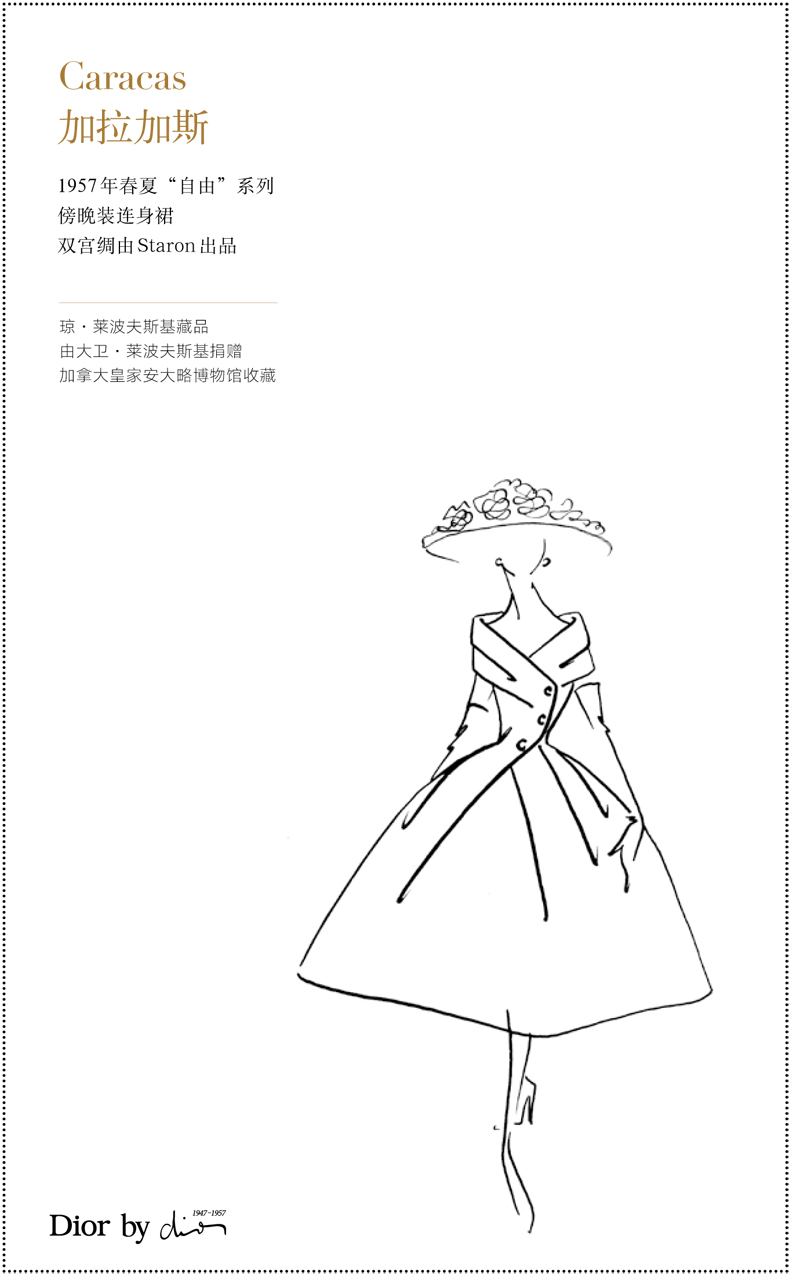

Late Afternoon-Evening

Christian Dior’s late day dresses were masterpieces of femininity and ingenuity that fused history and modernity. He introduced the cocktail dress in various lengths, and borrowed ideas from modular sportswear, suggesting an overskirt could also be worn as a cape.

Corset

Christian Dior’s silhouette was based on a corseted, concave torso. It raised the bust and flattened the stomach and accentuated the waist and hips. It fastened tightly with hooks and eyes, making it impossible to dress alone.

Hemlines

Throughout the 1950s, the press and public focused on the minutiae of Christian Dior’s fluctuating seasonal hemlines to be sure they would never be out of fashion.

Christian Dior and Modern Dressmaking

Christian Dior’s fashions were constantly remarked upon as technically extraordinary. He said, “My return to long-forgotten techniques raised a host of difficulties…none of my staff had any experience with them.” However, the ateliers swiftly developed signature cuts and construction techniques needed to achieve the New Look and to give his models more “presence.”

Corsetry and Boning

Since World War I, foundation garments had been made primarily with new elastics, but Christian Dior revived the art of cut, shaped, and boned corsetry.

Linings

Emulating dress linings of the 19th century, the House of Dior sewed the outer cloth and sheer organdy lining as one. This gave the dress body and held it in place.

Pleating and Darting

Christian Dior creatively integrated pleats and darts within the design to control fullness and subtly sculpt the dress.

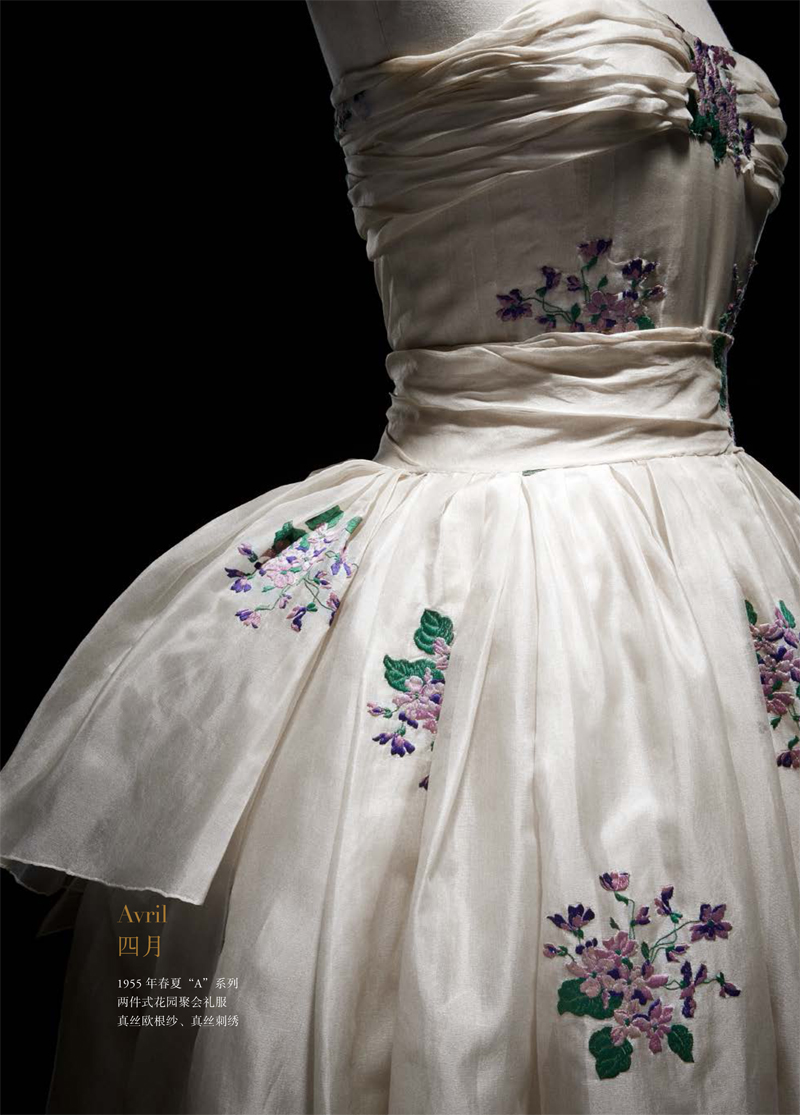

Two Bodices, Two Occasions

Christian Dior took inspiration from 19th-century fashions and offered designs with multiple parts for different occasions. This two-piece dress has bodices for late afternoon and evening, both with vertical seams for shaping. The signature boned corset configures the torso, aided by an attached petticoat with pleats, darts, and rows of nylon horsehair.

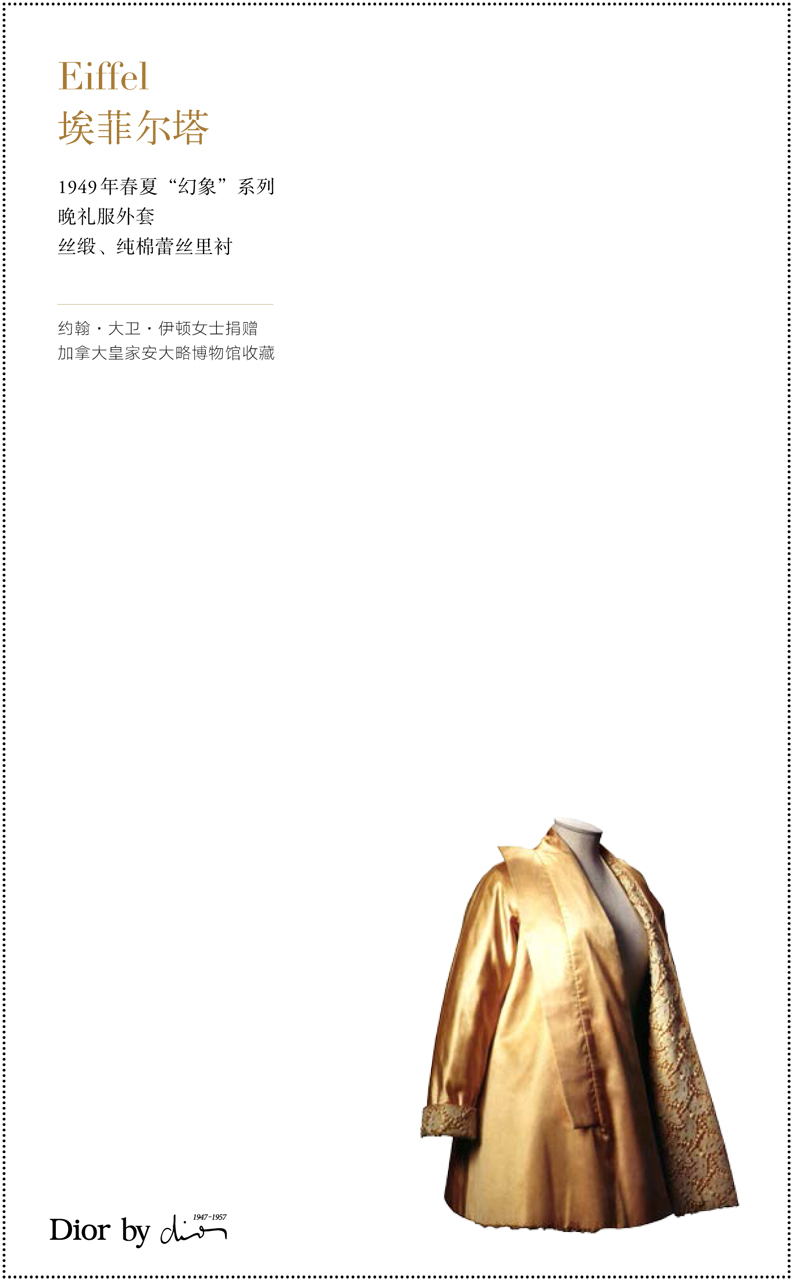

Evening

Christian Dior’s designs drew upon historical styles that reflected great moments in French design and society. He loved the 18th century, with its panniers (side hoops) and classical revival influences; the Second Empire (1852-1870), with off-the-shoulder dresses and wide crinolines; and the Belle Époque (1871-1914), with elongated, corseted torsos and daring décolletages. He drew freely from all, creating ravishingly elegant gowns.

Crinolines and Petticoats

The mid-19th-century invention of the steel crinoline eliminated the need for heavy layers of petticoats to achieve volume. Christian Dior’s crinoline petticoats were built into the dress. Five layers of cotton tulle were stiffened with crin (stiff nylon braid), to construct light-weight, voluminous skirts.

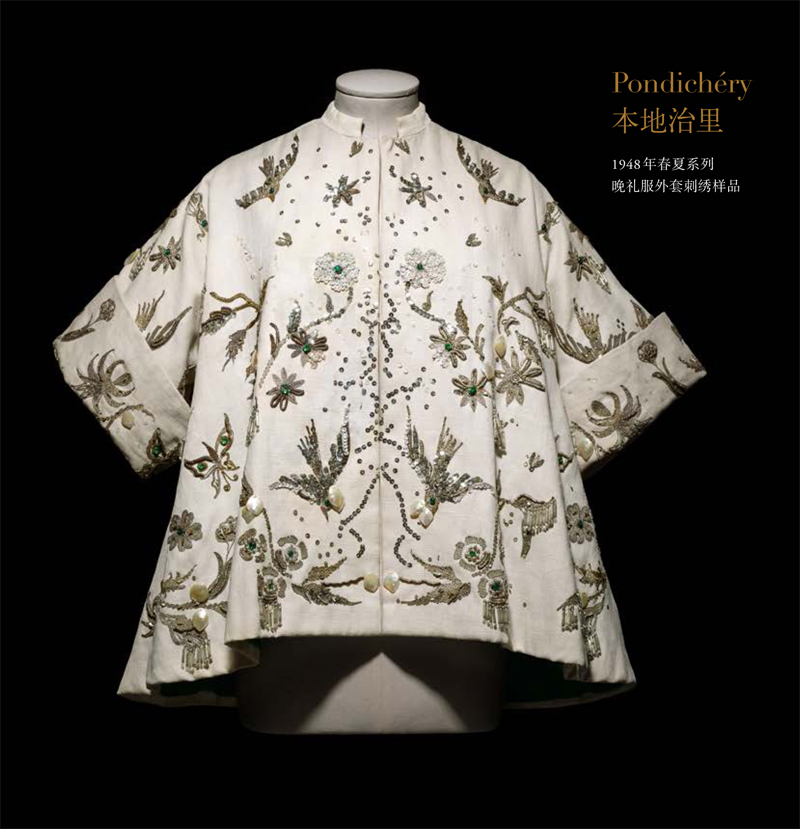

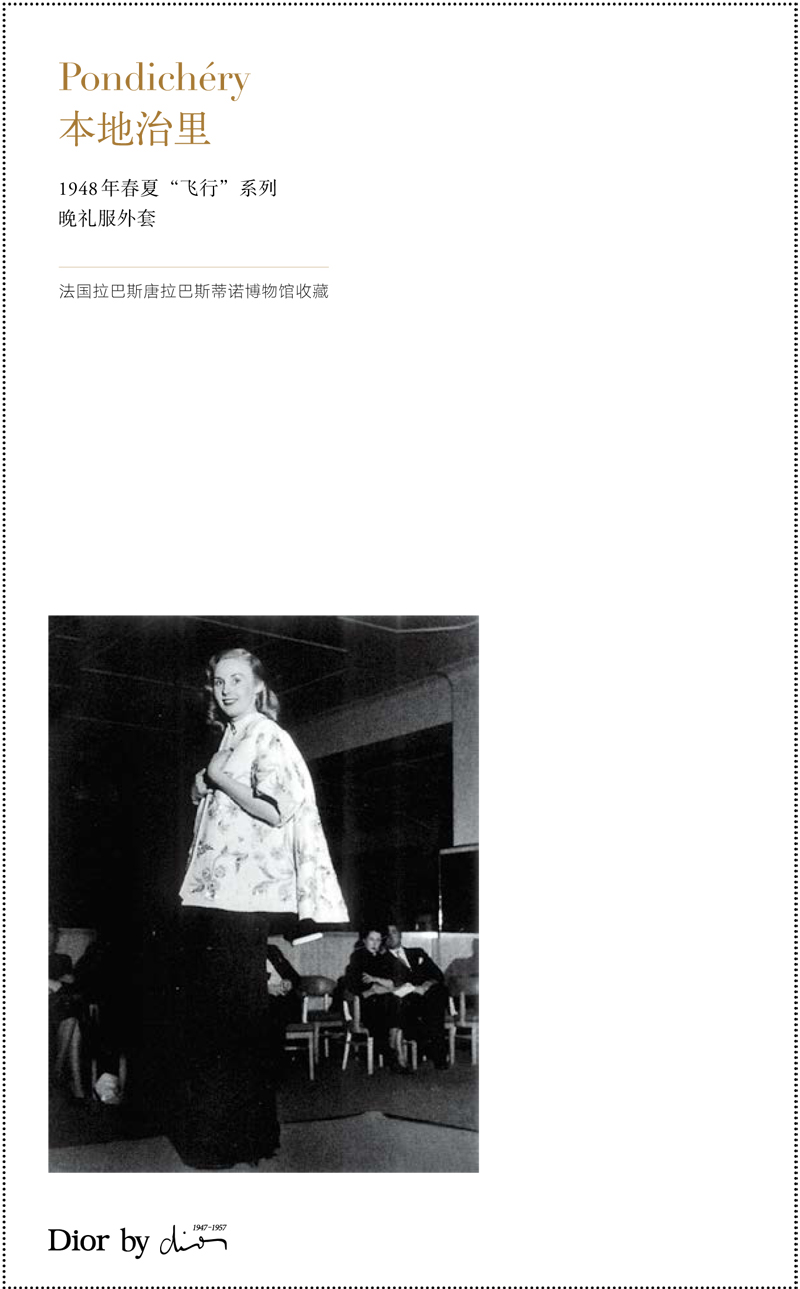

Name: Pondichéry

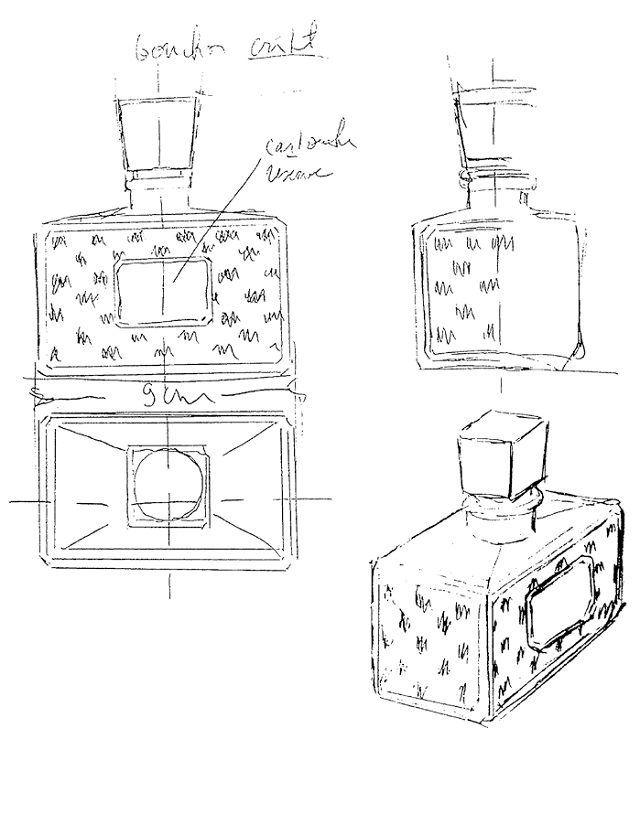

Miss Dior with original packaging, 1949

Etched glass, paper, silk

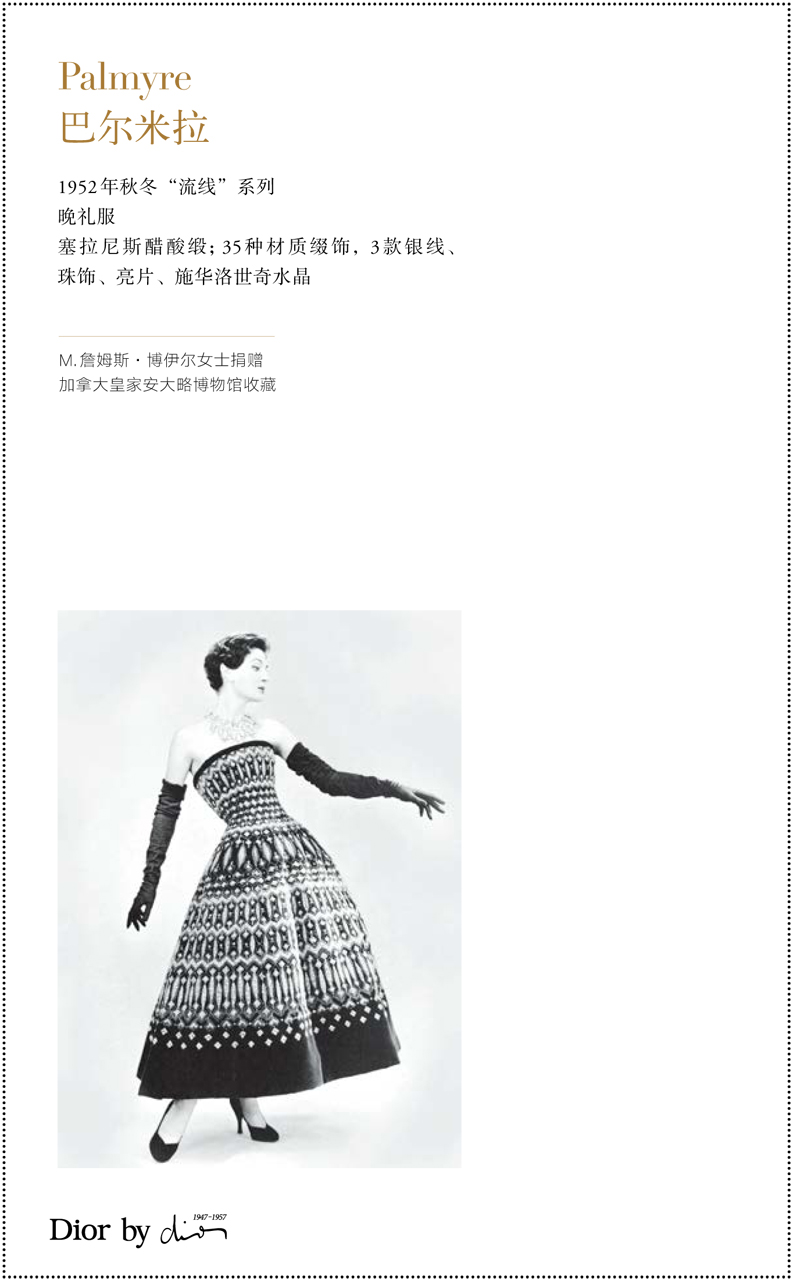

Name: Palmyre

Line: Profilée Autumn-Winter 1952

Occasion: Evening dress

Atelier flou:Germaine

Mannequin: Alla

Textile: Celanese acetate satin by Robert Perrier; 35 various materials, 3 silver-wrapped threads, beads, sequins, Swarovski® crystals, embroidery by Ginisty et Quénolle

Gift of Mrs. M. James Boylen

970.286.3

On loan from the Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto

Pay attention to us

×

Pay attention to us

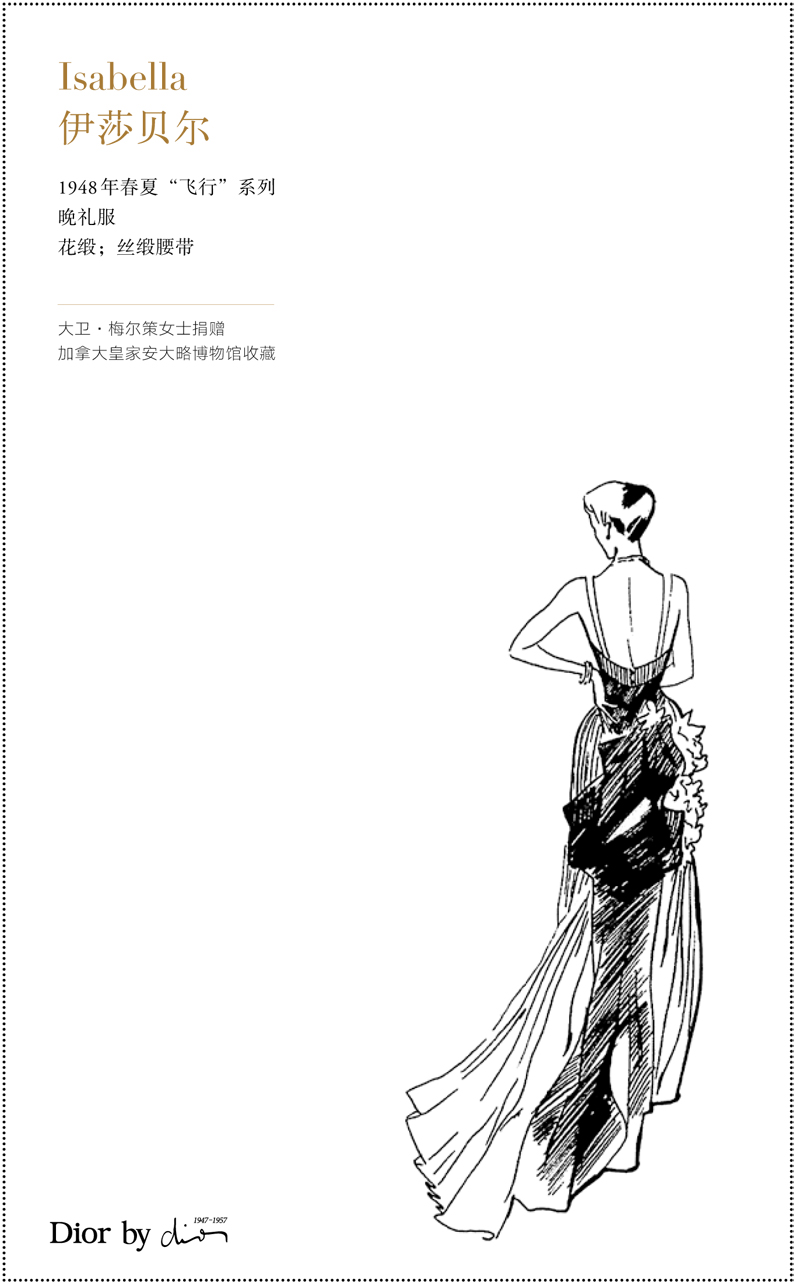

×